Pot vs. Column for Whiskey Production

Written by Scott Schiller – Executive Director

September 13, 2024

The pot still is known for having a higher degree of control and a greater diversity of spirits that can be produced, while the column still offers speed, efficiency, and consistency with the more straightforward addition of automation.

I can already feel the tension as some distillers read this title. Having launched over 50 distilleries during the past 16 years, this subject comes up a lot. While not as contentious as the merits of ricking versus palletization, this debate can get emotional enough that facts can get lost a bit. I would like to ask you to set aside the legitimate questions about artistry and tradition, and I encourage you to keep an open mind about the real merits of each option. While I have no bias as to which one you choose, I’d like to make sure you appreciate the boots-on-the-ground practical differences before making a decision.

A Simple Overview

Pot stills work well when making products that do not need to age. They allow you to make generous heads and tails cuts and run as slowly as possible to make very clean, high-proof spirits for vodkas (with an offset vodka column) and gins. Because pot stills are batch processes that start at low and finish at high temperatures, they tend to separate and concentrate heads on the front end and tails on the back end, whereas continuous stills do not. In continuous stills, because the final product is pulled off at one set temperature, heads are not as prevalent, and some heads remain in the final product to become future notes in the barrel.

What follows are the key considerations when choosing which system is best for you.

Define Success

Knowing where you want to end up personally and professionally helps shape the dynamic of art versus commercial. Elements to consider include featured product types, revenue/profit goals, and ideal exit pathway: generational or sale. If your business model relies on steady 10% year-over-year growth or you desire an exit, a column still may be your obvious choice. For every project of ours where a strategic entered via investment or acquisition, a column still was the very first conversation when figuring out plant growth, even for American single malts. The lack of ability or delayed ability to scale your current offering significantly lowers the multiple your business will warrant.

Create a Financial Model

It is always wise to plan for success and acquire as close as possible for your year 10 OPG (original proof gallons/OLA (original liter of absolute alcohol) production forecast based on a single shift. Adding shifts and extra fermenters is relatively easy and requires minimum downtime. Upsizing ancillary support equipment such as a boiler and steam piping is costly and can mean extensive downtime.

When it comes to determining a simple break-even analysis, a well-made 500-gallon pot still averages $180–$250,000, while a 12” column still averages $225,000. (Of course, there are lots of variables and options that drive price, such as the degree of copper used and the number of plates added.) Also, remember it is not a 1:1 ratio of size to price, meaning a 1,000-gallon pot still is not twice the price of a 500-gallon pot still and a 24” column is not twice the price of a 12” column. At the same time, larger stills require larger ancillary equipment, from cookers to fermenters to boilers to chillers. However, for every project I’ve worked on where the client chose the next size down, they always wish they had gone up.

Liquid Development

It is well supported that pot stills can offer greater flexibility and an enhanced degree of control when distilling. This may be particularly important if you intend to distill multiple mash bills, frequently innovate, or offer one-off releases. However, once you dial in a flavor profile, the objective is repetition, an attribute that the column still does beautifully. If whiskey is to represent less than half of your annual output, a pot still is likely your natural better choice regardless of flavor direction.

When it comes to targeted minimum age, pot stills have a slight advantage in that their output tends to age more quickly than column stills. This aspect relates to the pot’s control/refinement capability to offer finer heads and tails cuts. It is generally accepted that pot stills can provide a palatable bourbon in two years, while a column still would require an additional year to meet similar characteristics.

OpEx

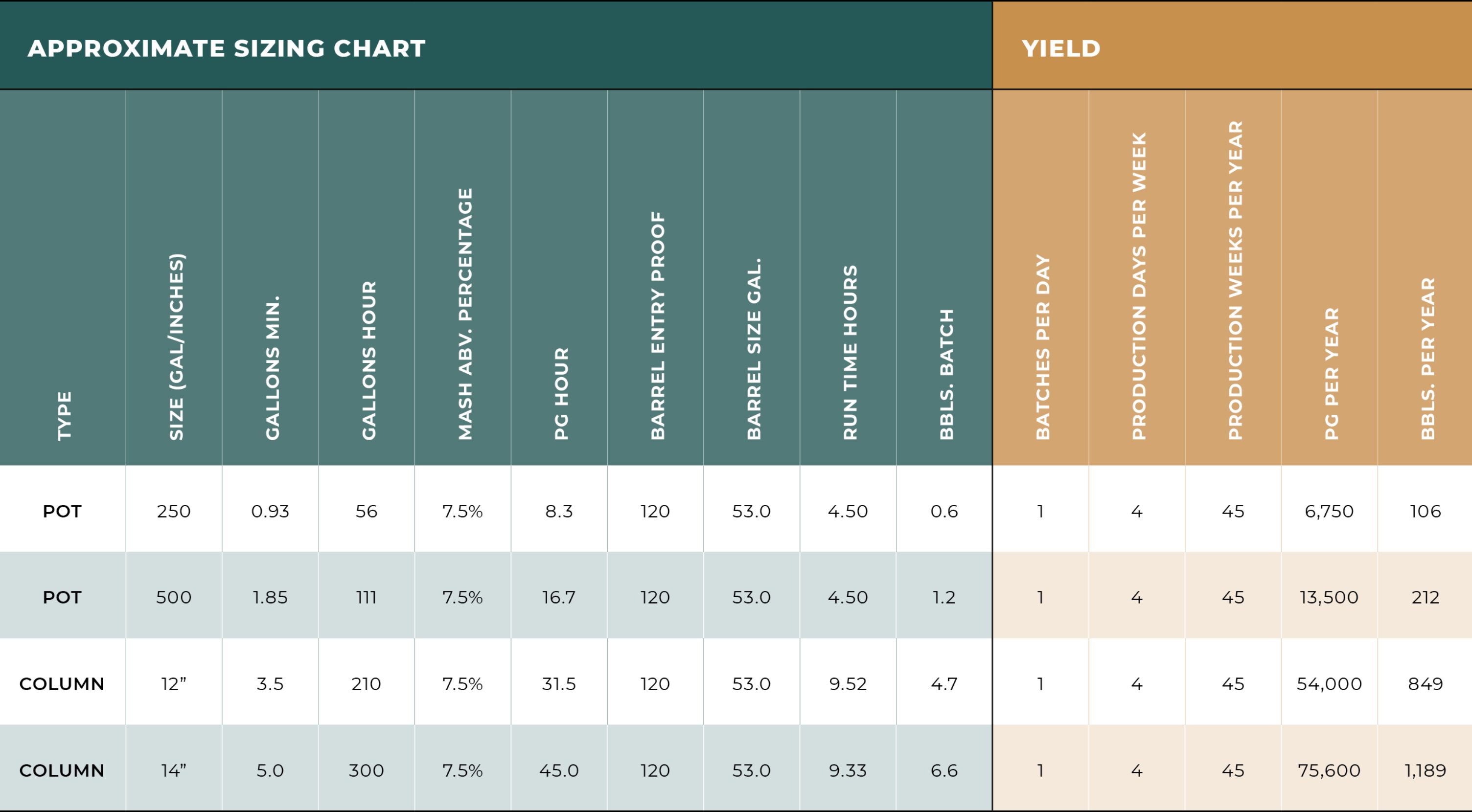

When it comes to cost, the column is the clear winner for cost per proof gallon when operator time is considered; this is magnified with any degree of automation. Referring to the chart provided, a 12” column still is nearly four times more efficient than a 500-gallon pot still, yet both require the same number of personnel to operate them. This is why so many established distillers switch or add a column still. When efficiencies are considered, the break-even analysis to add a column still is typically under two years.

Parting Wisdom

I love tradition and think pot stills are beautiful, but don’t let this drive your decision. Remember, only a tiny fraction of your customers will see your still, and it is a very rare individual who decides which spirits to buy based on the setup it was made on. That said, both have benefits. If cost is not a barrier, a super-ideal setup involves a column followed by a pot still that can act as a doubler in a full cycle or as a stand-alone pot still.

Finally, keep your facility from determining your production needs. Remember, you are a distillery first; margin matters. Don’t choose a location with extensive height restrictions or that does not allow for expansion.

The table below will help set the table using a Vendome Copper & Brass system.